Thursday, May 3, 2012

The Disturbing Death of Junior Seau

When I became a sports copy editor, I thought it was the best job I could possibly have in journalism.

I had worked as a general assignment reporter prior to that time, and I covered many depressing stories. I figured sports was all fun and games, and I welcomed it. Red Smith wrote that people go to sports events to have fun, and then they pick up the newspaper the next day to read about it and have fun all over again. That was pretty much how I viewed it.

Sure, I knew it wasn't fun for the teams that lost big games, and it wasn't fun for their fans.

But it wasn't the end of the world, either. It wasn't life and death. The sun (as Annie observed in the musical that was named for her) will come up tomorrow. Bet your bottom dollar.

I quickly learned, though, that sports isn't all fun and games all the time. It is deadly serious business for some folks. It is a huge, often insatiably ravenous beast, and there are those who become consumed by it.

Wait 'til next year. That has long been the defiant rallying cry of the runners–up. Except for those who were retiring, there would be another opportunity.

And when athletes finally hang it up, there frequently seems to be a second career for them. It is true that some athletes retire to live out their lives in relative obscurity, but others become coaches or commentators. Some become successful businessmen. A few go into politics.

Usually, as I say, there is that encore for the ex–athlete that can partially provide whatever he has lost because of his retirement.

I guess what is needed varies from one individual to another. Some need that adoration of the crowd. Others need the money. For some, it is the camaraderie of their teammates.

And most athletes find some kind of substitute in their post–playing career lives. Most of the time, that substitute probably doesn't come close to making up for what has been lost. Professional sports is a big stage with a bright spotlight and a huge, adoring fan base.

For an athlete like Junior Seau, who played in at least part of 20 pro football seasons and was named All–Pro a dozen times, the financial rewards of an athletic career are like winning the lottery every day, the cheers are loud and unending, and the closeness one feels with one's teammates probably can't be matched in any other occupation, perhaps not even military service.

I gather, from what I have read, that he missed it all. Maybe it had been a part of his life for too long. Maybe he did not know how to function without it.

After all, one does not become a professional athlete without spending many years on the other levels — college, high school, even junior high and middle school.

I don't know how many years Seau played football, but he was only 43 when he apparently shot himself in the chest yesterday. His professional playing career and his college career would have accounted for more than half his life by themselves — and it is reasonable to assume, I think, that Seau must have played the game for at least half a dozen years before that.

He may well have played football for three–quarters of his life.

From what I have been hearing in the last 24 hours, Seau struggled to find his niche in life after football. Apparently, he never found it. In the absence of any other explanations — like issues with drugs or alcohol or overwhelming debts — one must conclude that there was nothing that could meet his needs the way football did.

He may also have suffered from the kind of brain injuries that we hear mentioned so often in connection with football players.

And brain injuries are deceptive because there is still so much about the brain that people do not understand. Outward appearances are often unaffected by brain injuries, and, to a casual observer, Seau looked the same as always — a little older each time we saw him, but that happens to everyone.

My grandmother had a series of what were called at that time mini strokes. She didn't look any different to me, but she often spoke about these things that were in her head.

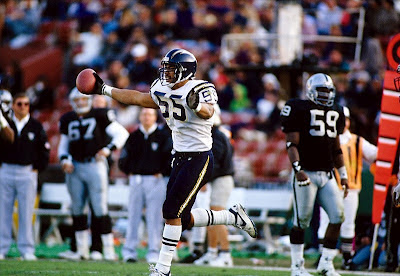

Perhaps Junior Seau had a similar sensation. He played linebacker, and linebackers are subjected to all kinds of violent hits on the field. It is reasonable to wonder if he, like so many other former athletes, suffered from chronic repetitive brain injury.

In most, if not all, of the 50 states, a suicide is also considered something of a homicide so, by law, an autopsy must be performed on the victim, and an autopsy on Seau can go a long way toward answering the unanswered questions.

Because he shot himself in the chest, Seau's brain can be examined, and perhaps some things can be learned from this tragic chapter in American sports history.

Perhaps something good can come from something so unspeakably bad.

Labels:

autopsy,

brain injury,

death,

football,

homicide,

journalism,

Junior Seau,

NFL,

sports journalism,

suicide

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment